Irene Jay Liu leads Google News Lab, part of the Google News Initiative, in the Asia Pacific region. An experienced political, investigative and data journalist, she was a 2017 finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in national reporting as part of the Reuters team that documented widespread cheating in U.S. college admissions.

Now, with News Lab, Irene promotes innovation and the use of technology in newsrooms. We talked to her about the dizzying pace of change in Asia, building a united front against misinformation and why journalists in the region are so willing to experiment.

What did you do before you came to Google?

My first full-time reporting job, in 2007, was eliminated by budget cuts before my first day. That was my introduction to the industry. Luckily, I landed a job in Albany, New York covering politics. It was a perfect introduction to modern reporting: I filed for the newspaper, ran the political blog, did radio bits for NPR and was an on-air reporter for the local PBS station.

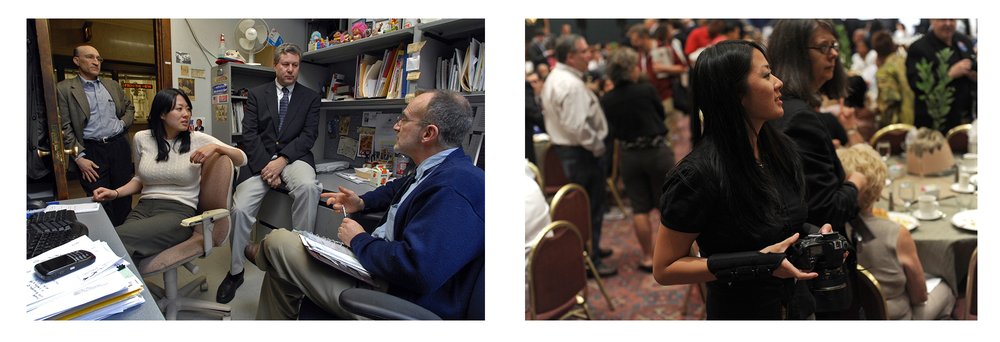

Covering New York state politics for the Albany Times Union

In 2010, I moved to Hong Kong to work for the South China Morning Post. There was something about Asia, and Hong Kong in particular, that drew me to the region — we didn’t know how the story would end. The intervening 12 years have proved that out. History took a very different turn than anyone could have predicted. So it’s really been an education.

Later I moved to Reuters, where I led development of Connected China, an immersive data-driven app, and then worked as an investigative reporter on their enterprise team. So I’ve also had the luxury of being part of ambitious, innovative data projects.

What are some challenges journalists face in the Asia Pacific region?

Change is the only constant in Asia Pacific. We’re seeing more and more pressure on journalists and the erosion of press freedom, not only in Asia, but globally. Despite this, there’s a strong sense of mission and purpose — that the work needs to be done. What has always amazed me is how newsrooms here are willing to collaborate with Google — and each other — to problem-solve and innovate. There’s this agility that’s really inspiring.

What do you think fuels that willingness to experiment?

I think it’s that history is moving at such a fast clip here. Journalists in the field can see the connection between freedom of expression, freedom of the press and the stability of their democracies and societies, because they remember a time when things were very, very different. They’ve seen the threat of misinformation and how it can be a matter of life and death, especially in the pandemic.

So there’s this visceral need to make it work, a sense that “we don’t have a choice, we have to figure it out as an industry.” Otherwise, the trajectory of history can change very quickly.

Can you give an example?

CekFakta in Indonesia launched ahead of the presidential election in 2019. It was really just a few journalists and folks from the nonprofit sector who came together and said, “We have an election coming, misinformation really affected thelast one. We need to take a stand.”

Because of their hard work, on top of everything else they’re doing, they convinced 24 news organizations — top publications that are constantly competing — to work out of the same room, collaboratively fact-checking presidential debates, and again on election day, to counter misinformation as it appeared.

What are some other ways News Lab works with journalists in the region to address misinformation?

Misinformation is top of mind almost everywhere in the region, and journalists feel as if it’s their cross to bear.

One project we recently supported in the Philippines is #FactsFirstPH, a project to connect journalism with the rest of the society ahead of their national elections. A coalition of news organizations came together to collaborate on fact-checking, working in tandem with researchers who analyzed patterns of misinformation, and then partnering with civil society organizations to amplify those fact checks, and with the legal community to hold candidates accountable.

We’re seeing more of this multi-sector collaboration. That’s what’s encouraging: experimentation, collaboration and the embrace of technology to tackle these issues.

Are we better equipped to address misinformation than we were a few years ago?

There’s greater awareness, but it hasn’t translated into institutions gaining trust. People are just more skeptical. That’s the challenge newsrooms face.

What’s interesting in Asia is that you have people coming online for the first time, so there’s an opportunity to develop awareness and resistance to misinformation from the start.

In India, we’ve piloted this approach through FactShala, which teaches news and information literacy to first-time internet users. Employing a curriculum designed from a baseline study of first-time internet users, Factshala partners with trusted sources — civil society organizations, nonprofits, community workers, educators, journalists — to get the word out in multiple languages.

Are you optimistic about the future of journalism?

I am. I miss being a reporter every day, and I’m constantly humbled and inspired by the journalists I have the privilege to work with here. Their ingenuity and tenacity, in the face of sometimes overwhelming adversity, is the reason I believe journalism will thrive.

And there’s so much that we at Google can do to support this work. As long as we listen to the journalism community and respond to what they need, there’s a lot we can achieve together.