Our new Bay View campus is on track to be the largest development project in the world to achieve Water Petal certification from the Living Building Challenge, meaning it will meet the definition of being “net water positive.” That important sustainability effort moves us closer to our 2030 company goal of replenishing more water than we consume. But what exactly does “water positive” mean at Bay View? District Systems Water Lead Drew Wenzel dove into that question head first.

Let’s get right to it: What does “water positive” mean?

“Water positive” at Bay View means we will produce more non-potable water than we have demand for at the Bay View site.

Hmm, let’s back up: What’s non-potable water again?

There are a couple of types of water. There is potable water, which is suitable for human contact and consumption, and there is non-potable water, which is not drinking quality but can be used for other water demands like flushing toilets or irrigation.

Typically, buildings use potable water for everything. At Bay View, we have an opportunity to match the right quality of water with the right demand, and only use potable water when it’s necessary. And by over-producing non-potable water, we can share such excess with surrounding areas that might otherwise rely on potable water for non-potable needs.

So basically, are we helping the water system save high-quality water?

Right. In California, we’re years into our most recent drought. We’re only going to see increasing pressure on water resources. Regional and State water agencies are working hard to secure the potable water supply. We believe we can best support these public-sector efforts and increase potable water supply by using non-potable water where we can.

So how did we get to water positive for Bay View?

This may be surprising, but it actually all starts with the geothermal energy system. Typically, removing heat from a building is done through evaporating a lot of water via cooling towers. At Bay View, instead of doing that, the geothermal system removes almost all heat by transferring it into the soil beneath the building. This system eliminates at least 90% of the water needed for cooling, or about 5 million gallons of water per year.

Ok, we start by reducing water use. What’s next?

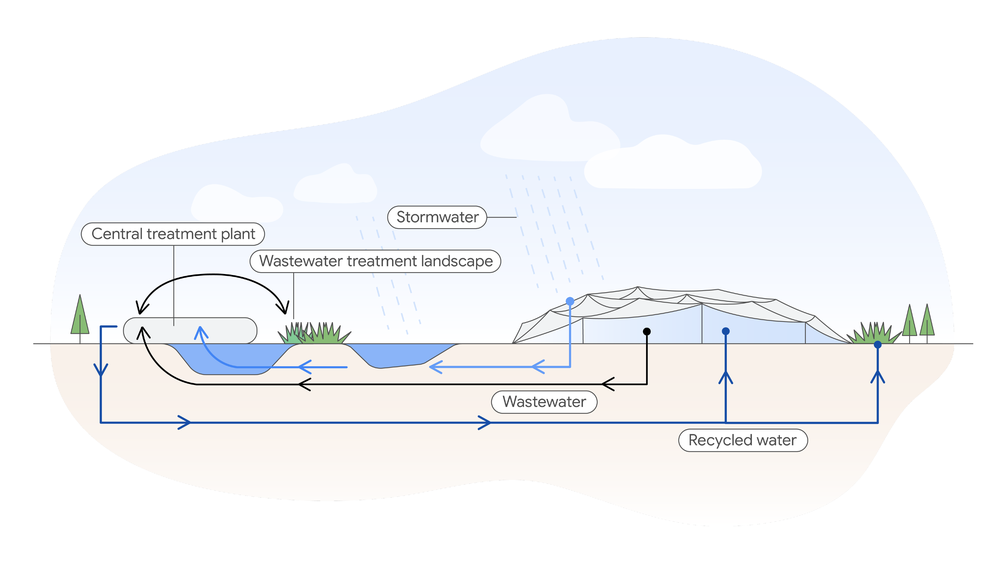

After improving the water efficiency as much as we could through the geothermal system and other measures, we looked at the water resources we have on site. By collecting all of our stormwater and wastewater and treating it for reuse, we are able to meet all of our onsite non-potable demands.

How do we treat it?

Stormwater treatment starts with the retention ponds that collect rain. Water from these ponds is slowly drawn down and pumped to a central treatment plant, where it goes through several stages of filtration, treatment and disinfection.

All of the wastewater — from our cafes, restrooms and showers — is collected and sent to the central plant, where it undergoes two stages of filtration and treatment. From there, the water goes out to a field of reeds that naturally pull out nutrients, creating a perennial green landscape that supports local wildlife. Finally, the water is sent back to the plant again for final treatment and disinfection.

The final output from both stormwater and wastewater treatment processes is recycled water that meets State regulations for non-potable use.

What happens if we don’t have enough non-potable water at any given time?

If our recycled water tank doesn’t have enough non-potable water to meet campus needs, it will fill up with potable water. At that point, everything in the tank would be considered non-potable because it has been mixed. Again, this isn’t the best use of high-quality potable water, and it’s something we’ll work to avoid.

If we create extra non-potable water, how can we share it?

This is something we’re thinking through, and there are a few ways we could go about it. The easiest way would be to export it to adjacent properties for irrigation to water something like a baseball field. That would require a relatively minimal effort of adding pipes.

Another way would involve potentially working with a local municipality that has a recycled water system, creating additional redundancy and resiliency within that system.

Aside from sharing extra water, Bay View already helps by treating and reusing its own water instead of adding demands to municipal systems. That leaves capacity on the system for the rest of the community and allows water providers to focus their time and resources on other needs across the water system.

Thinking beyond Bay View, is “water positive” important in places that aren’t in a drought?

Definitely. There are many cities that have combined sewer and stormwater systems that can be overwhelmed by excess water from buildings or large storm events. That can cause back-ups and flooding into the streets. Water positive systems, like the one at Bay View, can help communities and developers avoid placing additional pressure on municipal water systems.

Can any development site be water positive?

While a system like Bay View’s might not make sense for every project, there are different scales and variations of onsite water capture, treatment and reuse that are valuable, even if a building doesn’t get to official water positive status. Every little bit is going to help.